Blog Post series

- How to optimize .net development using .net core 2.1 and C# 7.2, introduction to fundamental concepts

- Introduction of working with

struct. - Working with

struct, a closer look (this post)

Introduction

It’s time to take a closer look at the code and find out the core mechanics of working with struct in C# 7.2 and .net core 2.1.

First, we will make a quick recap of the new ref and in keywords.

Then, we will take a look at a class that will be used to store and retrieve easily the objects and see how we use it to manipulate the objects.

Finally we will see some pitfalls to avoid.

Quick recap of the ref and in keywords

For those who are not familiar with the new feature of C# 7.2, let’s make a quick recap of the ref and in keywords. You can also find the full documentation about this here.

Say you have this class:

public partial struct Vector3

{

public double X;

public double Y;

public double Z;

}

Now you want to code a method that makes an addition of two vectors:

public partial struct Vector3

{

static Vector3 Add(Vector3 a, Vector3 b)

{

return new Vector3

{

X = a.X + b.X,

Y = a.Y + b.Y,

Z = a.Z + b.Z

};

}

}

In this implementation we have two similar problems:

- When you will call the

Add()method, theaandbobjects you will pass will be copied: that’s the basic behavior of value types. You may argue that it’s not a big deal for such a small type considering a 64-bits pointer will be 2/3 of it, but that’s not the point right now. - You will also have to create a new instance that will store the result and return it to the caller. This instance will also be duplicated at call site.

So we are likely dealing with 4 allocations, for a simple addition, these allocations will be made on the stack rather than the heap because we’re dealing with value types, but nevertheless: it’s not the fastest way.

Now let’s take a look at a different implementation of the Add() method.

public partial struct Vector3

{

static void AddByRef(ref Vector3 a, ref Vector3 b, out Vector3 res)

{

res.X = a.X + b.X;

res.Y = a.Y + b.Y;

res.Z = a.Z + b.Z;

}

}

Small changes, but big time differences:

- Adding the

refkeyword no longer copies the objects passed during the method call but passes a reference to them. - Using the

outkeyword that already exists for quite some time will avoid a new allocation, by storing the result directly in the destination object.

We got rid of these 4 allocations, fairly easy. The arguable trade-off here is not returning the result but using an out parameters, which is less convenient to use, but again, fast.

This implementation is not quite good yet, the ref keyword allows the AddByRef() method to modify the content of a and b (remember, they are references now), which is not appropriate in our case. This is why we should rely on the new in keyword instead, which passes a read-only reference of the object.

The correct implementation should be:

public partial struct Vector3

{

static void AddByRef(in Vector3 a, in Vector3 b, out Vector3 res)

{

res.X = a.X + b.X;

res.Y = a.Y + b.Y;

res.Z = a.Z + b.Z;

}

}

This is not the place of in-depth explanation about how the in keyword behaves, but be aware that you may not always get a performance improvement because of the so-called defensive copy mechanism.

The RefArray<T> class

I’ve quickly developed a small class RefArray<T> (source code here) that wraps an array and allow access using the new ref keyword.

Here the implementation:

public class RefArray<T> where T : struct

{

public RefArray (int initialSize = 16)

{

Count = 0;

_data = new T[initialSize];

_dataLength = initialSize;

}

public int Count { get ; private set; }

public int Add(ref T data)

{

// Check grow

CheckGrow();

_data[Count] = data;

return Count++;

}

public ref T this[int index]

{

[MethodImpl(MethodImplOptions.AggressiveInlining)]

get

{

if (index < 0 || index >= _dataLength)

{

throw new IndexOutOfRangeException();

}

return ref _data[index];

}

}

private void CheckGrow()

{

if (Count == _dataLength)

{

var newLength = (int)(_data.Length * 1.5f);

var newArray = new T[newLength];

_data.CopyTo(newArray, 0);

_data = newArray;

_dataLength = newLength;

}

}

private T[] _data;

private int _dataLength;

}

The code is fairly easy, internally it’s an array of T and you have two methods to interact with the array:

public int Add(ref T data)to add an item to the array.public ref T this[int index]to retrieve a reference to the item (to access or modify it).

Let’s take a closer look at the array accessor implementation

public ref T this[int index]

{

[MethodImpl(MethodImplOptions.AggressiveInlining)]

get

{

if (index < 0 || index >= _dataLength)

{

throw new IndexOutOfRangeException();

}

return ref _data[index];

}

}

You may notice something that wouldn’t be obvious to understand at first: there’s only one get method, no set!

The reason is simple, as a reference to the object is returned you don’t need a setter, you will modify the object directly.

RefArray<T> is the class that I used in the benchmark of the post #2 of this series, you could elaborate something more feature complete, but it serves the primary purpose.

A concrete example of using the Array<T> class

The struct version of the Stock type is using the Array<T> class to store all the trades the stock owns.

public struct StockStruct

{

public StockStruct(string name)

{

Name = name;

_tradeArray = new RefArray<TradeStruct>();

}

public string Name { get; }

private readonly RefArray<TradeStruct> _tradeArray;

public int TradeCount => _tradeArray.Count;

public ref TradeStruct GetTrade(int index)

{

return ref _tradeArray[index];

}

public int AddTrade(ref TradeStruct trade)

{

return _tradeArray.Add(ref trade);

}

}

As you can see the code is fairly simple, the Array<T> class is encapsulated and we make sure we use the ref keyword to add/get Trades.

It worth to mention that Array<T> is a class, so it’s stored in the heap, which is what we want, what matter is that all struct objects are stored sequentially in the the private T[] _data; field, which is what we’re looking for to speed things up.

The ref readonly pitfall

When passing or returning a reference to an object, you have the possibility to specify the readonly keyword to make sure the callee won’t be able to modify the given instance.

This will work fine with struct containing mainly public fields, as we demonstrated in the Vector3 struct. In this case the compiler can check that any attempt to modify any field and return an error during compilation.

If your struct is using properties, things get trickier, internally a property is a method, so you’re able to modify the content of a given instance even if you’re accessing a property through its getter.

As of today, the compiler reacts in such case with a pretty brutal approach: a copy of your readonly object is made and returned to the callee in order to make sure the initial object won’t be modified.

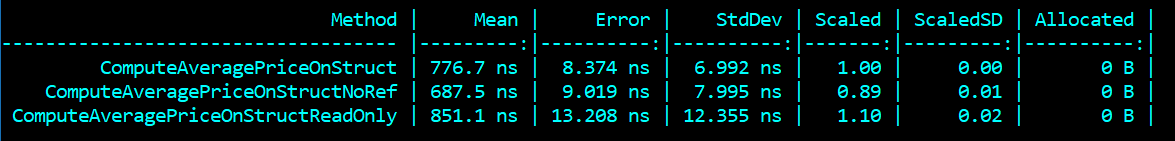

As we can see below, the benchmark run with a readonly version of the structure access is slower than both ref struct or struct copy !

General rules

- Use a struct to store plain, publicly exposed data, if you get into a more complex type with properties, then working with struct may not be the best fit for you.

- If you’re willing to expose read-only object, consider the

readonly structkeywords during the declaration of a new type, it will be considered as immutable, then the compiler will stay away from defensive copies, ensuring you the best performances. - Profile! The theory is what it is: theory. I won’t replace the reality of a profiled piece of code! Sometime the copy of a struct will be faster than a reference, especially for small objects.

Immutability in C# is not managed as well as in C++, for instance, if you consider advanced scenarios with struct and readonly or in keywords, I strongly encourage you to thoroughly read the official documentation about ref/in/readonly struct keywords.